This interview was conducted on May 14, 2019, and has been edited for clarity and length. Disclosure: David Spitzley is an employee of the Washtenaw ISD IT department.

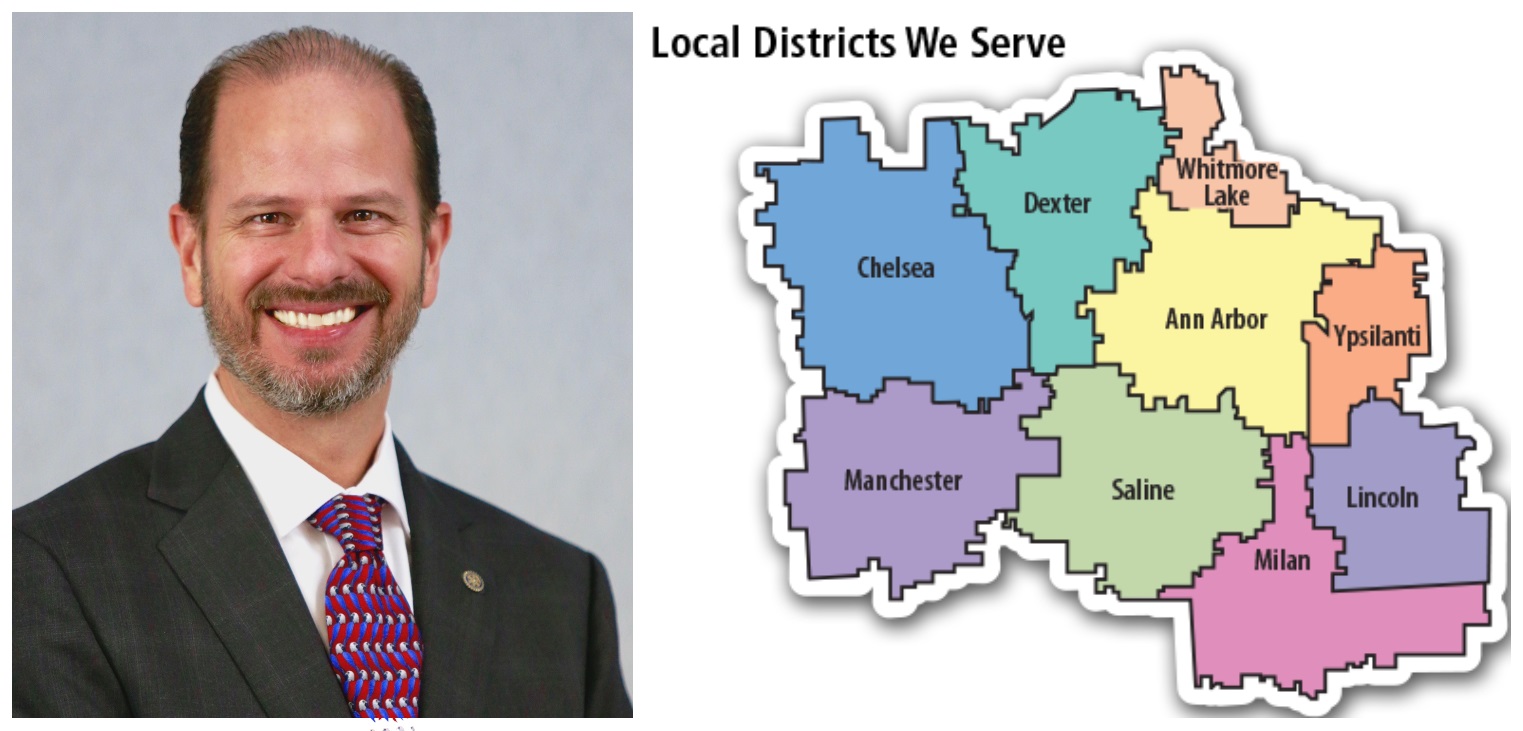

Michigan’s Washtenaw Intermediate School District (WISD) is an educational service agency (ESA) supporting the nine public school districts in Washtenaw county (Ann Arbor, Chelsea, Dexter, Lincoln, Manchester, Milan, Saline, Whitmore Lake, and Ypsilanti), as well as the charter schools throughout the region. WISD has spent the last several years grappling with the inequities of public education in the county, which features both Ann Arbor, a majority white district drawing its students from a very highly-educated and wealthy community associated with the University of Michigan, and Ypsilanti, a majority black district with a high percentage of poor and special needs students. In the process of working to address the problems in the county, WISD has consciously undertaken what it terms an “Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice” mission (EISJ), led by its board and by Superintendent Scott Menzel. Dr. Menzel kindly agreed to sit down to discuss WISD’s efforts in this area, as well as the broader picture of how public schools can and do deal with injustice, both outside and inside the classroom.

David Spitzley: When did we first adopt at the ISD the Equity, Inclusion and Social Justice (EISJ) mission, and what triggered that formulation and the decision to move on it?

Scott Menzel: It was here before I started. If you look at our Education 2020 plan, which was approved by the board in 2009, one of our core values is “equity, inclusion and social justice”, and I think it’s prefaced by “quality”, so it was in the Education 2020 plan, and on the minds of both people within the Intermediate School District and our constituent districts in Washtenaw county. The extent to which we actually spent time asking ourselves the question “how are we living into that stated value”, that kind of shifted and evolved. I got here in 2011, and we worked closely with Ypsilanti and Willow Run on the consolidation process [footnote in 2011 the Ypsilanti Public School District and Willow Run Community Schools districts, facing declining enrollments and severe financial stress in the aftermath of the real estate crash, merged to form the new Ypsilanti Community Schools district, with extensive assistance from the Washtenaw Intermediate School District]. You can see the stark inequities in Washtenaw county, and as we engaged in some of that work the external facing part of our equity work was readily apparent.

What became increasingly apparent post-consolidation when we started looking at our internal culture and climate, and the diversity of our staff and their experiences here at the ISD, is that we weren’t attending to how we were living it out in our own organization. So in 2015 Washtenaw county did the Child Opportunity Index mapping with the Kirwan Institute out of Ohio State, and by census tract identified where things were. There was a growing Washtenaw county focus on these topics. And on 2016 Opening Day here at the ISD we said we’re going to look more deeply into how we’re doing this work and how as an organization we’re embodying those values, and that it starts with each individual. The Commit sign we have out in the atrium here is from that opening day. So we’ve been very intentional on the inward part of the work since 2016.

David: I went through the Board Goals and reports, and it looks like 2016-17 was when that became an formal goal. Things definitely changed in how the goals were formulated in the succeeding years. So, having established that this was something that would be on the organizational agenda at a deeper level, what sorts of policies and programs have we put in place to support the goals that we were laying out in the Board agenda?

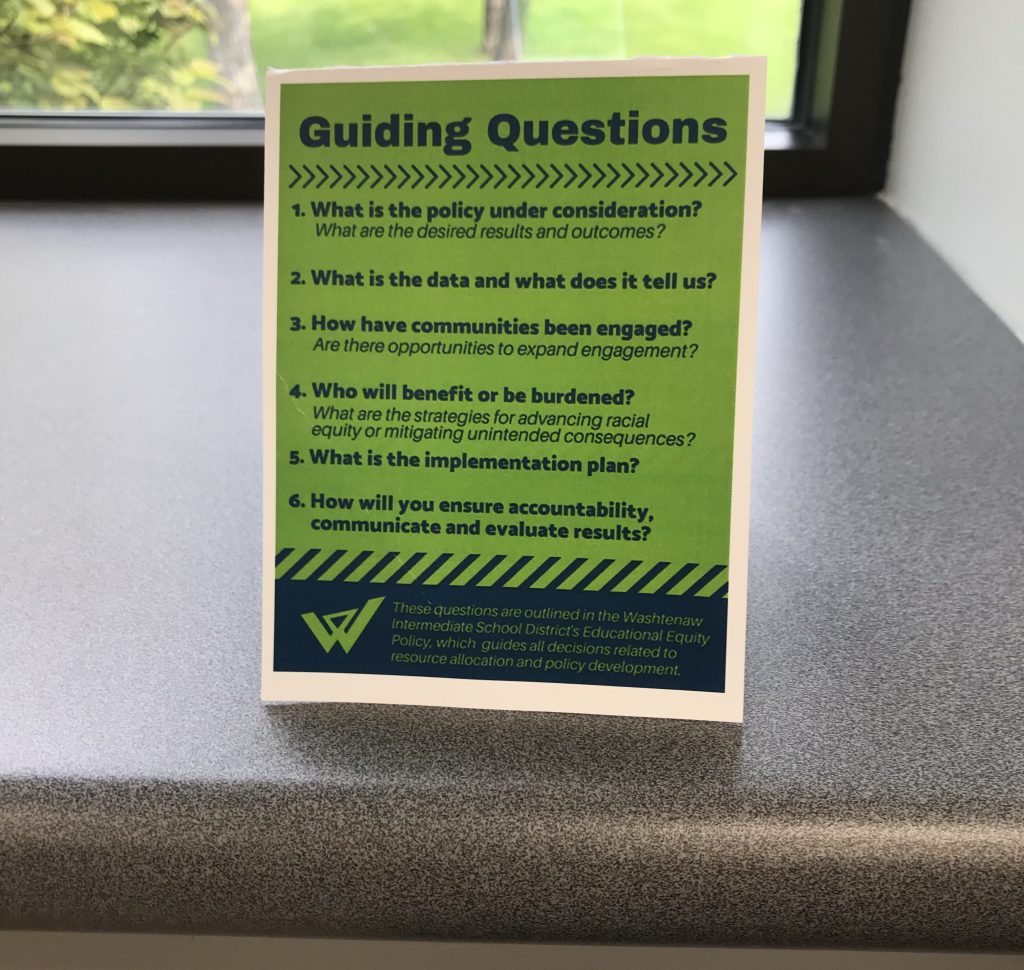

Scott: Last June the board adopted an Educational Equity policy, and we spent a number of months looking at examples of educational equity policies from both ESAs and local districts around the country to get an idea of what ours might look like. At the same time, Washtenaw county had engaged the Government Alliance On Race and Equity, and they had a toolkit that is used, and that was incorporated into our Equity policy as well. The Board formalized our commitment in our Ed 2020 plan, but it went even deeper with respect to that commitment by adopting the Educational Equity policy, where the expectation is now established that, not only for policy, but funding decisions as well, we’re going to hold ourselves accountable for the ways in which we’re disrupting and dismantling systems that deny access and opportunity for kids of color, kids in poverty, and kids with IEPs[footnote Individual Educational Plans, a federally mandated annual document created for children with disabilities to ensure they receive the special education supports necessary for them to be successful in school].

David: And that’s where the the questions from the little standee come from. That’s a really good set of functional guidelines for how you make this stuff matter in the basic nuts and bolts of policy making. I was impressed when I saw that we came out with those; I think you presented them at Opening Day. Even if it’s basically a checklist, it’s an important checklist to have, and putting that in as an explicit expectation was a pretty strong move by the organization.

So what form did the Educational Equity policy take aside from the guiding questions?

Scott: I would say a couple of things. The Board acts through policy in its decisions, and also in adopting a budget. For the last few years, the Board has allocated funding for EISJ work, roughly $100,000 per year, and it’s not that we don’t do other things that are equity focused, but there was a line item that was created for that, and we’ve been investing pretty heavily in professional development for our staff. Some of it has been through the Justice Leaders work, and that continues to evolve; we’re on cohort 10.

Awesome learning with #JusticeLeaders today. Intersectionality & recognizing we are at different spots on the SJ continuum were some takeaways. Powerful series that all #miched Ts would benefit from. Sustained PL w/ a cohort of individuals ready to be okay w/ discomfort @WashISD https://t.co/odNLLAteYD

— Sarah Giddings, NBCT (@sarahyogidds) February 7, 2019

Each individual is looking through a different set of lenses, we’re all born into this world, based on our family circumstance, where we grew up, whether it was a different state, socioeconomic status at birth, all of those things influence how we view the world – and the training we’re providing is causing many of our employees, especially our employees who identify as white, but also our staff of color, to really critically examine the ways in which our structures and systems advantage some and disadvantage others, and not just accept things on face value that “this is how things should be” or “this is how it has to be”, but really questioning “why is this operating the way it is?” “who benefits?” “who is burdened”, and what can we do differently about it.

When we had a special request for funding consideration from one of our local districts, we said unless you frame it using these six guiding questions we’re not even taking it to our board. So we’ve kind of shifted the way that we we think about the decision making process to ensure that we’re holding ourselves accountable for how we’re asking and answering these six guiding questions and tying it back to our educational equity policy.

David: How would you say our efforts on this level compare with what is happening statewide and nationally at other educational organizations?

Scott: It’s a difficult metric, in the sense that there are others on this journey with us, there are some districts and ESAs that have been on this journey longer than we’ve been on it, and there are many that haven’t started or have barely scratched the surface, so based on the colleagues that I know working on this, and the deep commitment of our board, I would say that while we are not the leading organization, we are a leader among ESAs, and there’s a role to play here with respect to how we support our constituent districts, because these are not easy conversations to have.

So, I have to tip my hat to the board, because none of us within the organization could do what we do in this arena without 100% support from the board, and we have that even though some of the board members have changed in the last few years. That’s always a worry, when you have new people at the table, do they share the vision that was articulated by the prior board, and in this case they do.

David: Getting into slightly trickier areas here, has the effort evolved as white supremacist and nativist movements have reemerged in the American political environment over the last couple of years? While it’s clear that the Inclusion mission in particular is not solely about race or class, but includes things like Special Education status, this particular aspect of it has become more fraught recently.

Scott: I would say the current political climate, even prior to the election in 2016, did set the stage for our explicit commitment to how we’re going to do this work, and who we value and how we value people within our organization and in the larger community. And so, the reemergence of the white supremacist subculture and how all of that plays into our conversation here, we see it in so many ways. What’s different and unique about this point in time in history, is that it’s explicit. It always was there under the surface, it’s in the very fabric of the way this country was established, and we’ve never righted the wrongs of the genocide of the indigenous population, and the enslavement of a population from Africa on which the wealth of this country was built. And so, in some respects, the 2016 election, and the things that surfaced around that, Charlottesville for example, created an opportunity for us to really expose how the systems operate, and once you can bring that into the light of day, it gives you the opportunity to dismantle, disrupt, and then recreate something that’s socially just and more equitable.

David: Are we receiving much pushback on what we’re doing? How much of it is opposition to EISJ as a concept as opposed to opposition to specific policies which might be either uncomfortable or inconvenient? How much big picture opposition are you seeing as opposed to specific?

Scott: I’m going to say something that may get me in trouble. We live in a, generally speaking, progressive liberal environment. That’s not the entire county, we have conservative elements, but overall when you think of Ann Arbor you think of “liberal progressive”. However, liberal progressives aren’t always the best champions for equity, inclusion, and social justice. They may be champions if you’re going to march, or carry a sign, or put on a bumper sticker, but when it means actually changing the way things are structured, we get a lot of NIMBYism, “not in my backyard”. I was in two different meetings today where the concept of housing affordability was on the table. Housing affordability is a direct by-product of housing policies, and redlining happened in Washtenaw county just as it did in urban areas, so we’re just as guilty in Washtenaw County of creating advantage for people who have resources, and happen to be predominantly white, compared to those who aren’t. So when you look at the demographics in our county, even the redlining that happened in Ypsilanti, these are things that because they’re so uncomfortable, to look in the mirror honestly and know that we’ve been complicit, people don’t want to talk about it.

David: And that obviously gets into the current issues of zoning: Do we build up? How do we handle greenspace versus development versus transportation? There are lots of people who want to protect their own property values or their particular vistas.

Scott: “I’ve worked hard to be able to buy a house in this community to go to this high-quality school, and I should not be denied this opportunity, or have it somehow lessened, because we’re going to bring ‘those kids’ from some other community that didn’t have that same advantage – if they would just have worked harder, David…”

David: Or whatever myth the people are adhering to…

Scott: Fill in the blank, that’s the conundrum here in Washtenaw county, we say the right things, but talk is not action.

David: Have you found your status as a educated, upper middle class, white male, and the attendant privilege, created any problems in being able to serve as an advocate for these things? Are you finding resistance based on that? Have you hit your head on any posts without realizing it?

Scott: [laughter] My experience, and I can only speak for me, I think there are two things. One, I’m a white male in a position of relative power and privilege within the organization. I didn’t grow up that way, but it doesn’t really matter, in this country I check the boxes that give me the greatest level of advantage. Based on how I view the world, that also means I have a higher level of responsibility. In that vein, I see my responsibility as calling out the ways the system advantages people who look like me, and disadvantages people who don’t look like me. I also have two daughters, and I know that in this society being born male is an advantage over being born female. That’s not a socially just society, because gender, race, how tall or how short you are, should not determine your life prospects, socioeconomic status. Children don’t deserve their circumstance in birth. In a socially just world you wouldn’t be able to predict test scores, you wouldn’t be able predict any other life outcome based on any of those arbitrary variables or circumstances of birth. And so, because I had that advantage in this country, I have an additional burden and obligation to dismantle. I have an obligation to open doors for people who otherwise wouldn’t have doors open. I have a responsibility to make sure people are sitting at the table whose voices typically aren’t at the table. It means sometimes I need to step back so other people can step forward. But because I’m in a position of privilege and power, those are the obligations I have. If I fail to do so, then I have fallen short of the EISJ commitment we have in this organization.

David: As a practical matter what are you finding is the biggest obstacle? Do we have any programs or specific areas where we’re hitting walls, areas where we’re trying to work and it’s turning into a major push uphill?

Scott: Let’s break it down in terms of a debate that’s is ongoing. I don’t know if you’ve watched any of the RBG (Ruth Bader Ginsburg) films, but there are two. One is On The Basis of Sex, and that goes to her early career and some of the court wins related to gender inequality that paved the path for her ultimate rise to the Supreme Court. The other one is the RGB movie, which is more about her entire life. Both are really good to watch. Her approach to gender equality was incrementalist in nature. If you remember the 70s, people were marching in the streets for equal rights and there was a lot of energy around that. Ruth took a pragmatic approach to say, we need to look at the laws that have codified gender inequality, and brick by brick begin to tear down that wall. The same is true if you think about the civil rights movement in the 1960s, there were people who were revolutionary in nature, who took up arms to fight the man, and there were people who said we need to figure out how to work with the people in power to change the structure. There’s this dynamic tension, and I’m not going to say that one is right and one is wrong.

But even within our own organization, look at how we distribute special education funding. Arguably it’s not an equitable funding formula. It’s a formula that was developed in consultation with our nine constituent districts. It changed about 4 years ago, because the former process, while maybe more equitable, we gave everybody a fixed percent reimbursement of unreimbursed special ed costs, in order to do the fixed reimbursement percentage we had to have a lot of money in the bank because we couldn’t account for the variability. It didn’t make sense to keep money in the bank that was designed to serve kids, so we had to come up with a new formula. Four years into the new formula, it’s pretty clear the formula rewards those who can spend more. Who can spend more, David?

David: Those who have money already.

Scott: Those who have money already! That becomes part of the problem. Fixing it is not a simple solution. There are winners and losers, there are always winners and losers in the economic game. Even with the way schools are funded currently. Because if I’m a School of Choice district, and I’m a net winner, somebody else lost. So when we think about how do we ensure a more equitable distribution of resources, our board wants to tackle those questions, but they’re not simple solutions, and sometimes they take more time. So I suspect there’s frustration on the part of those who want us to move faster and more deliberately. I did have someone tell me as I was going on about dismantling and disrupting the systems, she said “Scott, be careful, there are still children in these school buildings”. If you dismantle the whole thing you don’t want unintended consequences that harm children in the process. So, being thoughtful and being clear about what the path is, not using it as an excuse to not act, because that’s a white dominant-cultural norm, right, in fact it’s a university norm here, we study everything to death. It’s our excuse for not acting because we need to study more. “What does the lit-ra-ture say, David?” And I sit in so many rooms where that’s what the conversation is, “what does the literature say?” And that’s what we’re going to do next is see if anyone has studied this, and what they’ve learned from their study. Two years later we’re looking at what the literature says again, because you know what, there’s been new literature since the last literature. So there needs to be a balance between understanding what we need to do, and the direction we’re heading, but acting. And sometimes we’re going to act and screw it up, so let’s learn from it, and pick ourselves up and continue on the road to justice, because the thing we can’t do is not act.

“Disproportionality is a practice, not an outcome.” Learning from Tabitha Bentley @WashISD as we look at our discipline, student perception, attendance, SAT, graduation rate, and post-secondary outcomes data through an equity lens. @cvannatter_wisd @OlmsteadBrayton @Heaviland pic.twitter.com/9qz6UaER9j

— Naomi Norman (@EdInnovates) March 1, 2019

David: So, for families not in our community, if parents or community members want to help schools in their area advance EISJ goals and try to work on improving access, equity and so forth, what are some ways they can do so that would actually be useful? Writing nasty letters can feel good, but isn’t always all that productive.

Scott: There are a couple of things that people can do. One, I would recommend that anyone download our Educational Equity policy, and send it to their superintendent and school board. There’s a misperception that educational equity is really only for ethnically and racially diverse districts. But white people have racial identity as well, and in fact problematic racial identity that we typically avoid. So whether you are a homogenous district or racially and ethnically diverse, everybody has EISJ challenges. Every district has poor kids, every district has kids with IEPs, every district has diversity represented within its walls. Being intentional about the kinds of questions you are going to ask yourself – what’s the policy under consideration, what is the data and what does it tell us – most school districts are dealing with issues around achievement on standardized achievement measures or achievement gaps, whether it’s a gender gap, or a socioeconomic gap, or an IEP gap, or a racial gap, what is the data and what does it tell us? How have we engaged people in those conversations? Schools are supposed to be democratic organizations, reflecting the interests of the community.

David: I imagine there are many administrators who may not agree on that point…

Scott: I think you’re right. But we do have school boards in place, and for superintendents and school administrators you get to make a decision. The school board sets the policy, you carry out the policy. If you and the school board are in agreement, life is pretty good. If you disagree, life can be pretty uncomfortable for the administrator. So when the community makes it clear that this is a value that we hold, that we want to ensure that all of our children have the opportunity to achieve their full potential, and that means that when some come to kindergarten less prepared because they didn’t have the same access and opportunity as those of their more affluent peers, what is it that we’re going to attend to as a district in order to ensure that that lack of access and opportunity doesn’t permanently diminish their capability to be successful in the system? So people can ask those questions, and then demand training.

At the end of the day, our history books don’t teach history in a way that causes us to look honestly at what really happened. It is a, and pardon the pun, whitewashed history, that makes white people look good all the time. And when you begin to do your own work as a person who identifies as white, and you really look honestly in the mirror in terms of white male privilege, you look in the ways that we codified in statute that advantage, look at representation in TV and movies, and just go back 50 years and see how we stereotyped people consistently. Look at an old western movie. I’ll never look at those “cowboy and indian” movie the same way again. Because what what we realize is, we were glorifying the people who were driving the rightful owners of the land off of the land so we could appropriate it for our own purposes. History doesn’t teach it to us that way, and so there’s a lot that makes it really uncomfortable, and the easy path is to say, “alright, we’re just going to do this, and go no further”, but if people in concert begin to say, “no, what’s right for our children, and the future of our country, is to really look in the mirror honestly”, and then figure out a collective way forward, creating that sense of inclusion or belonging, not including you at the table in a symbolic sense or a token sense, but inclusion as a sense of belonging, that everyone brings value to the table, and that we see them for their own inherent human worth and dignity. That’s a different conversation.

To me it starts with school boards and policy, because everything flows from that. Superintendents that ignore board policy get fired. It is a terminable offense. There are superintendents who have led this and got fired because their boards didn’t come along, there are superintendents who move down this road and had communities work to get them ousted because they didn’t support it. So, there is occupational hazard for anyone who engages in this work, but there was occupational hazard, and some people paid the ultimate price, for civil rights advocacy in the sixties. There were people who paid the ultimate price for advocacy for women’s rights, both in this country and around the globe. What do you value, what are you willing to die for, and at the end of the day in this organization we’re about the kids, and creating a better future for them. And that means taking some risks related to the kinds of decisions we’re willing to make to disrupt the system that we know only works to benefit a few and not all,.

David: Something I like asking people is “what don’t you get asked that you’d like to talk about?”

Scott: Let’s be clear, that the hardest place to do this work, is in high-performing, affluent districts. And we have that in our own county. It’s not hard to talk the talk, but it’s really hard to do the work that changes the game. And people don’t want to put it on the table. So for me that’s the biggest frustration, and even sometimes for me, I will be very careful how I frame something depending on the audience. I’m becoming less and less cautious about some of those things, but I also want to be invited to have the conversation. So it’s that dynamic balance between how far can you push. If you think about blowing up a balloon, there is a popping point. Balloons are great until they pop. So thinking about how hard can we push on the system without a collapse that disrupts the progress of the entire work and sets us back 20 years, that’s a question we don’t talk about often enough in my mind. But also calling out the question of privilege. White people, Robin DeAngelo’s book “White Fragility” calls it straight up, white people need to feel comfortable, and quite frankly we shouldn’t feel comfortable, we should feel really, really uncomfortable, because we perpetuate a system by ignoring the realities in front of us, and living in a mythological reality. In this country it’s about meritocracy. “Pull up yourself by your bootstraps, everybody has the same opportunity”. And it’s a lie.

So, I think calling it out, being courageous enough to do so, some days I have more courage than others.

David: I can understand that. You bring up the analogy of the balloon, and you have to worry about popping, but there’s that initial point where you gotta just force the damn thing open before you can start to blow into it. In some regards I think that making the mess on the carpet a few times, so people realize “ok, they’re serious about this”, and getting some support from groups that may be marginalized when they realize there’s an authentic effort being made to do something that would matter, is kind of the balloon opening initially.

If you could make one policy change that would apply nationally, school districts everywhere, to advance the EISJ agenda, what would that be? You can think big here, and obviously there’s no silver bullet, but maybe you can at least wing ‘em.

Scott: Money is not the end-all be-all, but resource allocation reflects values and priorities, and even with the School Finance Research Collaborative study here in Michigan, it surfaces that it doesn’t cost the same to educate every kid, so equal funding for all students is the wrong goal in Michigan and across the country. Funding our students based on their unique needs in order to help them achieve their full potential, there’s an economic imperative there. Our employers are clamoring for talent and they can’t find it, and then they point the finger at the public education system and say “it’s your fault”, but we’ve had a decade of disinvestment. How do you expect to disinvest in the infrastructure that’s preparing your future workforce, and then when you can’t find the people with the skills you need, blame the system you underfunded?

@WashISD Superintendent Menzel on how equity in education & our region’s workforce pipeline are tightly interwoven. @A2YChamber pic.twitter.com/wBZvxKsJkC

— Washtenaw ISD (@WashISD) March 18, 2019

But the funding shouldn’t be equal, the funding should be equitable based on the needs of the kids. We need to go beyond just what’s happening in the schools. This is about an ecosystem, it’s about housing, it’s about food security, it’s about how do we address the trauma that some of our kids experience, whether it’s physical, sexual, verbal abuse, whether they’ve witnessed violence in their home or their neighborhood, they’re bringing that trauma into their schools. We have so many things going on in the larger ecosystem that harm children, that we have to think about the policies in terms of how they intersect. But investing in children from conception to the time they enter college and careers, is a systems approach, and making sure that the funding is designed to meet the needs of the kid and not the needs of the adults in the system, and that it is variable not based on where you live, but on what your needs are when you come into the classroom, that would be a major policy shift, and an advantage for our system.

David: Well, that’s all I’ve got, so you’re free to go, sir. (laughs).

Scott: I appreciate the chance to talk about it. It’s worth noting that the national Association of Educational Service Agencies has an affinity group around EISJ. There are more than 80 people around the country who have signed up to participate in our affinity group. Some are just observers, they sit on the sideline and watch our online dialog, and a handful who go so far as to participate in web conference discussions.

But at the end of the day we’re also working to build a strong network in Michigan, and we’re growing the effort in Ohio, so this is the third year we will have a Midwest forum on Equity, Opportunity and Inclusive Practices (July 29-30) for educational service agency staff from Michigan and Ohio – we invite any others from the Midwest area who want to show up – and beginning to develop teams not only within our own organization but across ISDs and ESAs to enhance our capacity to serve our districts and our communities in an EISJ effort. So I think it’s growing and we all need to find the people we can lean on as we go into battle together.

David is one of the earliest writers for Torchlight, and also pinch hits on website support and editing/posting. He holds a PhD in Economics, which with $5 would get him a latte; sadly, he doesn’t even like coffee. He can be reached at dspitzley@torchlightmedia.net.