Civil Rights are the basic rights of a citizen of a given nation. They comprise those rights, freedoms, and standards of access without which one cannot participate meaningfully in the society of that nation–both the political society of laws, legislatures, and courts, and the civil society of moving around, speaking one’s mind, and existing in places open to the public. The right to life, for example, is the most basic of civil rights; obviously if one is killed, one cannot participate in society. But rights such as freedom of speech, assembly, and the press are all civil rights as well, because if one cannot speak freely without undue reprisal, one’s ability to participate in society is greatly diminished.

This definition, like the term itself, may seem extremely broad, and that’s partially because the term civil rights comes from an earlier attempt to distinguish such rights from political rights. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, thinkers of the time argued that they had full civil rights (life, speech, and so on) but not full political rights (voting, holding public office, etc.). For instance, although prior to the 19th Amendment women had freedom of speech and assembly, they didn’t universally have the right to vote: civil rights without political rights.

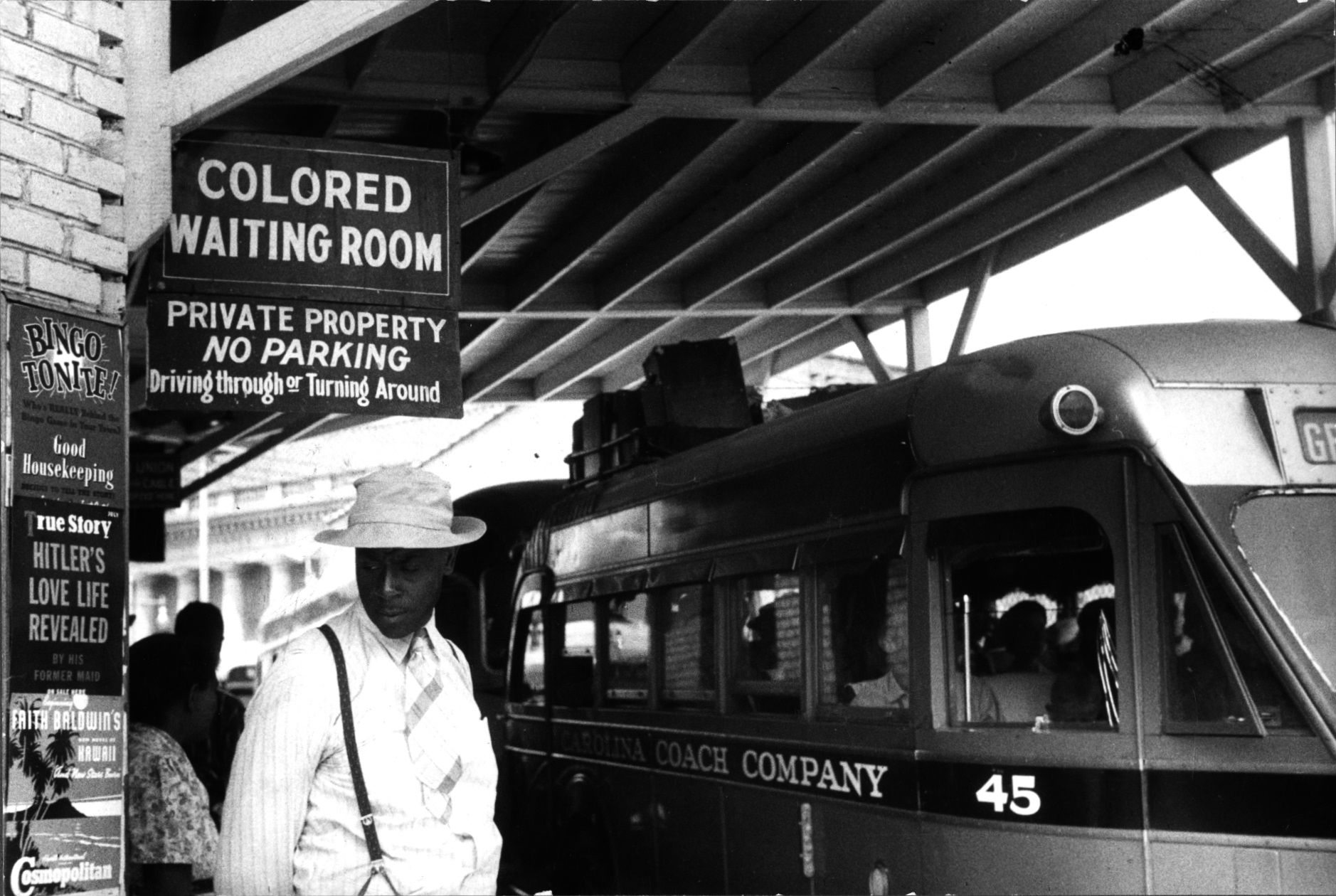

This distinction collapsed; it has proved all but impossible to be a full and equal member of society without full and equal participation in that society’s political system. The status of freed slaves following the end of Reconstruction provides a stark example: the Southern states immediately moved to deprive the freedmen of their political rights, which coincided with depriving them of their civil rights. Without political rights to protect them, civil rights proved to be nonexistent. Thus, a century later, we see voting rights–as political a right as you can imagine–wrapped up with the Civil Rights movement.

Civil rights tend to be negative rights, which means that they compel inaction, rather than action. For example, your right to free speech does not compel you to do any particular thing; rather, it compels the state not to interfere with your right to speak as you please. This contrasts with positive rights, which would compel people to act in particular ways; for instance, the right to an attorney compels the state to provide you with an attorney. That compulsion isn’t absolute: the state is not required to provide an attorney if you already have your own.

But the positive/negative distinction masks three difficulties. First, at what point does my discriminating against you impair your ability to function in civil society and, therefore, violate your civil rights? For example, consider hotels. If a single hotel in a single city won’t rent a room to to you, you can probably find lodging down the street, and though your rights have been violated, you can still mostly participate in society. If the majority of hotels in each of the majority of cities refuse to serve you, you effectively can’t travel anywhere without private lodging. You would have difficulty running for any kind of national office.

Second, at what point does an individual violating another individual’s civil rights compel the government to act in order to protect those rights? How many lunch counters have to refuse you service before the government requires them to serve you? The answer tends to depend on why they are not serving you: if you’re being rude to the staff, they’re fine to deny service. If you’re there with your same-sex partner, you have a discrimination case.

Third, at what point is the government obligated to not just protect your civil rights, but to actively shape society so that you can exercise them? Literacy is a strong example of this idea. Society requires so much reading that participating in it without reading is absurd; hence, we have public schools. Similarly, you can’t participate in society if you can’t reach society; therefore, we have public roads.

Civil rights in the United States are governed by a host of statutes whose strength is derived from several constitutional amendments. The first ten amendments comprise the Bill of Rights, which enumerates such well-known rights as freedom of speech and the right to a fair and speedy trial. The ninth amendment also stipulates that the other amendments are not exhaustive: there exist rights other than those defined in the law.

Further amendments established or strengthened civil rights for various groups of Americans. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments outlawed slavery, established that everyone born in the United States was equal under the law, and prohibited race-based voting restrictions. The 19th amendment extended voting rights to women, while the 23rd extended voting rights to residents of Washington, D.C., but only for Presidential elections. Finally, the 26th amendment set the national voting age at 18.